Kāhui Ako ki Orewa

Supporting and Empowering all tamariki and Kaiako to learn and achieve personal excellence/hiranga

Whakatauākī – Orewarewa whenua, puāwai māhuri.

Ngā Aronga – Focus Areas

Our Kāhui Ako ki Orewa kura will work together in a collaborative way with students/ākonga, parents, whānau and community to accomplish the achievement goals.

Ko Te Moemoeā – Vision

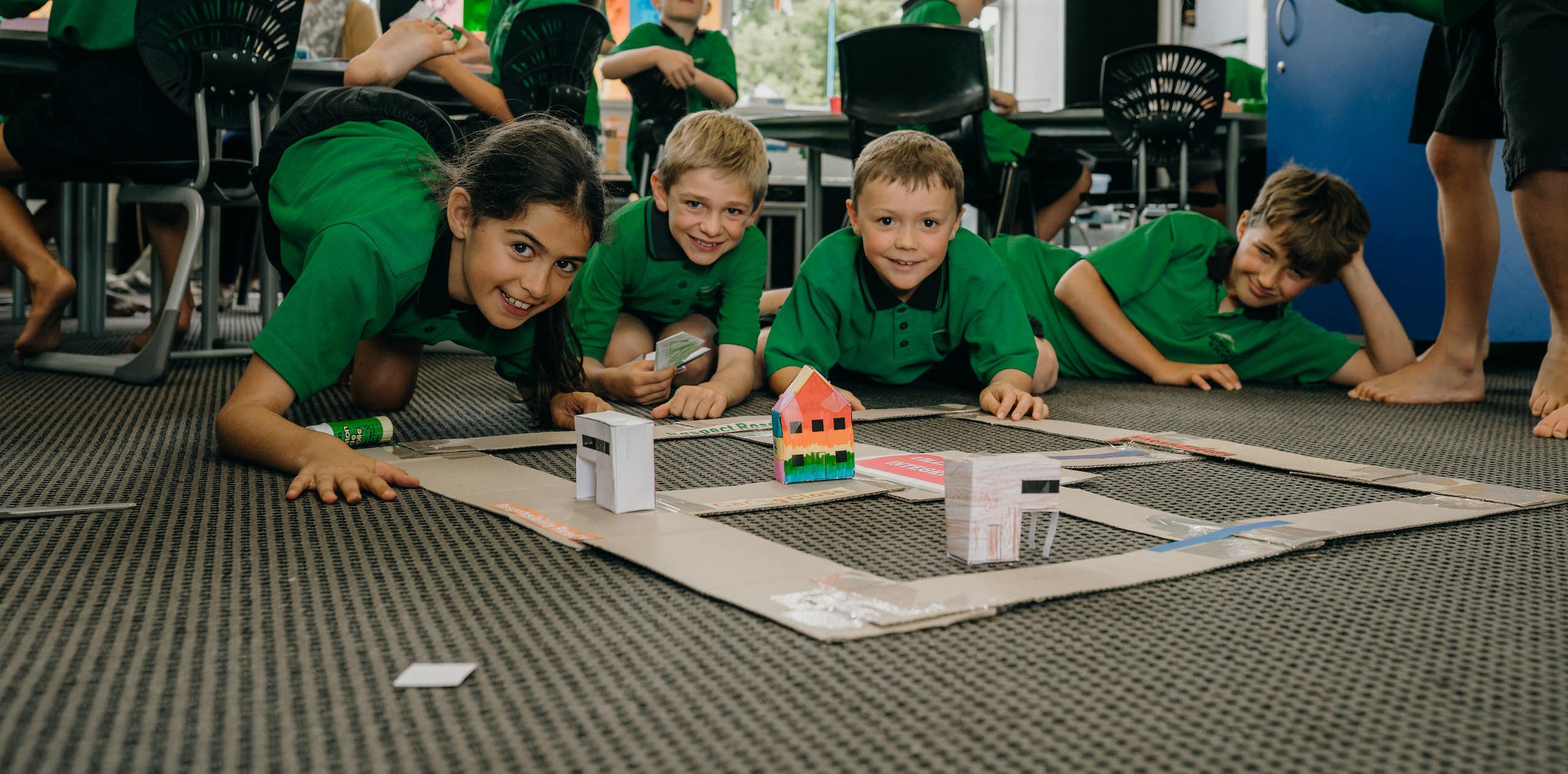

We will raise achievements for all students/ākonga in our Kāhui Ako ki Orewa by developing collaborative pathways for equitable learning and participation. All ākonga attending a school in our Kāhui Ako ki Orewa will receive quality teaching and support to achieve the expected progress.

We will do this through our four focus areas:

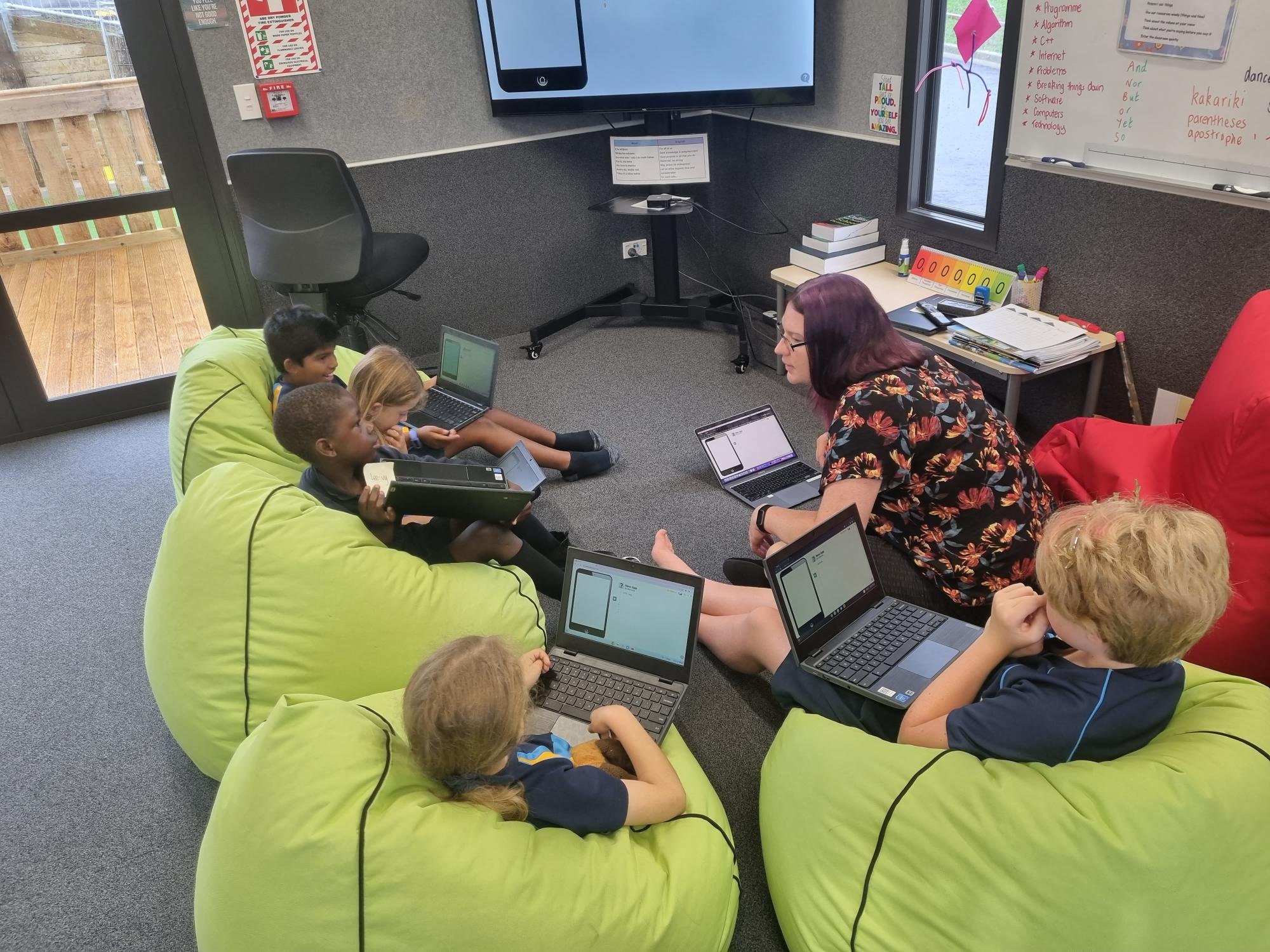

- Future Ready

- Te ao Māori

- Hauora

- 21st Century Learning

Ko Te Take o te Tuhinga nei – Purpose

The purpose of this website is to provide a description of the shared achievement challenges of the Kāhui Ako ki Orewa for its wider community including the parents and whānau of the kura, the students/ākonga, and the staff.

The plans on this website provide an overview that identifies how there will be a strong learning pathway for all learners to realise the potential of each child. A detailed implementation plan will be developed in the first phase of the work the community of learning undertakes.

Nga Kaupapa e Haere ake nei – Upcoming Events

Check out our events section for the latest information on events, training, meetups and more.